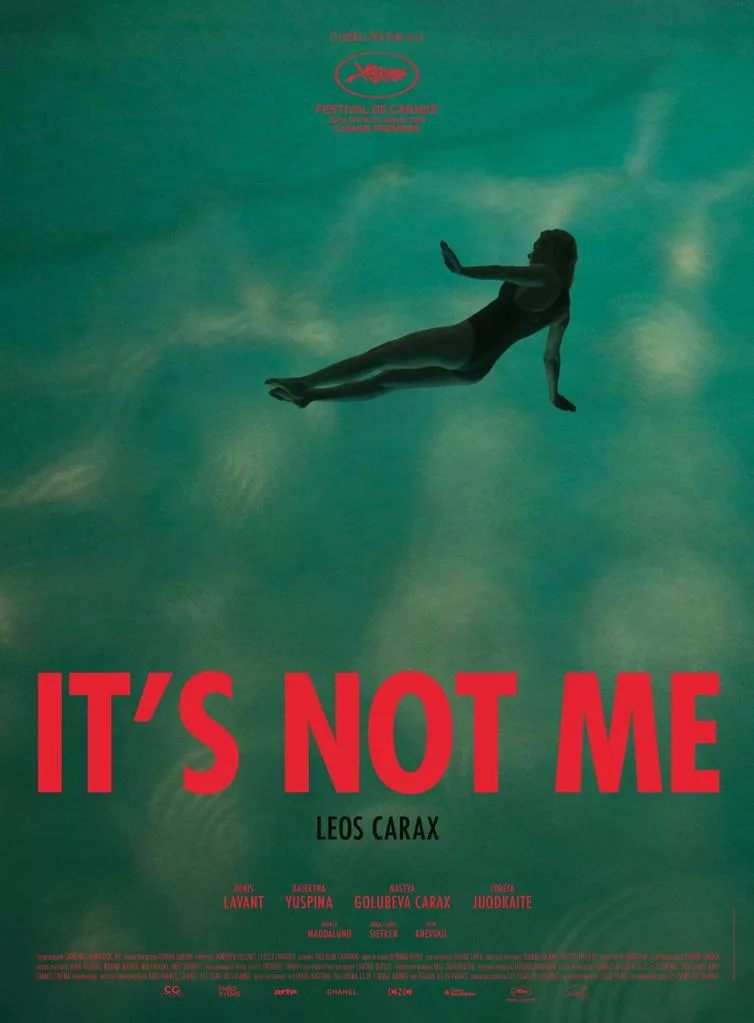

Although its release tonight on The Criterion Channel is likely to go unnoticed amidst the current onslaught of films competing for box-office titles and end-of-year awards, the arrival of “It’s Not Me,” the latest film from celebrated French filmmaker Leos Carax will be seen as a major cinematic event in the eyes of certain moviegoers. Part of this is because Carax, for all of his undeniable qualities, is not exactly the most prolific of filmmakers, totaling only six full-length features between his 1984 debut “Boy Meets Girl” and his most recent, the head-spinning “Annette” (2021) with a handful of shorts sprinkled in amongst them. Another part is that the project comes billed as a sort of cinematic self-portrait, a tantalizing notion considering the reclusiveness he has demonstrated throughout his career, even if said self-portrait only winds up clocking in at a mere 40 minutes. That said, there are more intriguing notions and examples of breathtaking cinematic style on display in the relatively brief running time than most films at two or three times that length are typically able to muster.

The original inspiration for this particular project was a proposed exhibition that never happened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris that would be a response to the question “Where are you at, Leos Carax?” His answer, following an initial “I don’t know,” is a heady collage that mixes together film clips (ranging from Eadweard Muybridge’s “A Horse in Motion” to Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” in addition to his own films), newly filmed sequences (including an appearance by Carax mainstay Denis Lavant as Mr. Merde, the character he played so memorably in the director’s contribution to the anthology film “Tokyo!”), archival footage and home videos, augmented by on-screen texts and an often chaotic soundtrack. The most obvious point of comparison is to “Histoire(s) du Cinema,” Jean-Luc Godard’s landmark and deeply personal multi-part meditation on the history of cinema—indeed, the late legend for whom Carax served as an actor in his finally-arriving-on-Criterion version of “King Lear” (1987), makes a brief appearance of sorts in the form of an answering machine message that he left for Carax.

Needless to say, anyone hoping for a straightforward “and then I did this …” exploration of Carax’s life and work will probably not find what they are looking for here. There are times when he is playful, as when he presents footage that he claims is of his father or when he suggests a certain kinship between himself and the famous comic strip character TinTin. There are times when he is angry, as when he presents images of atrocities ranging from the Nazi rally held in Madison Square Garden in 1939 to dead refugee children. There are moments of cinematic scholarship that find him drawing lines connecting key moments in cinema history and how they would go on to inspire him.

There are moments of mourning as well, most notably as he despairs over how the art of cinema as a whole has degraded over time and has lost some of its magic as a result—a question that he contemplates as images from that most haunting of cinematic visions, F.W. Murnau’s “Sunrise” is seen. As for the analysis of his own output as a filmmaker, he pretty much keeps it to a minimum, but even so, the brief clips of his work that we do see (especially the moments from the extraordinary Bastille Day sequence from his 1991 masterpiece “Les Amants du Pont-Neuf”) will make you want to rewatch them as quickly as possible. All of these elements are put together in a way that may seem haphazard at first but which goes on to form fascinating juxtapositions.

Perhaps inevitably, how one reacts to “It’s Not Me” will depend to a large extent on where you stand in regards to thoughts on Carax as a whole. If you have never cottoned to his work in the past or have not yet experienced any of his films for yourself, then it is more than likely that you will find most of this film to be largely incomprehensible. However, if you are one of those who finds Carax to be one of the most fascinating filmmakers of his time—and I would place myself in that camp—then I have a feeling that you will find it to be a striking cinematic tapestry that gives you an eye-opening look into the thinking process that has giving us so many great films.

As has been the case in those earlier films, Carax approaches his work with a striking emotional vulnerability that meshes beautifully with his undeniable technique and lingers on in the mind long after the end credits have run. (Speaking of which—if you are a fan of “Annette,” be sure to stay through them here in order to witness what is easily the most entertaining post-credits sequence to come along in a very long time.)

Whether one looks at it as a summation statement from an artist taking stock of their life and work at the end of their career or as another one of the brief cinematic diversions that he has taken on in between his feature projects, “It’s Not Me” is a reminder that Leos Carax is one of the most fascinating and formally interesting filmmakers working in the world today. In writing about his film “Pola X” in 2000, Roger Ebert praised Carax’s audacity by stating “You aren’t described as an enfant terrible at the age of 39 without good reason.” Carax may be 64 now but, as this film demonstrates conclusively, outside of the difference in age, that statement still holds.