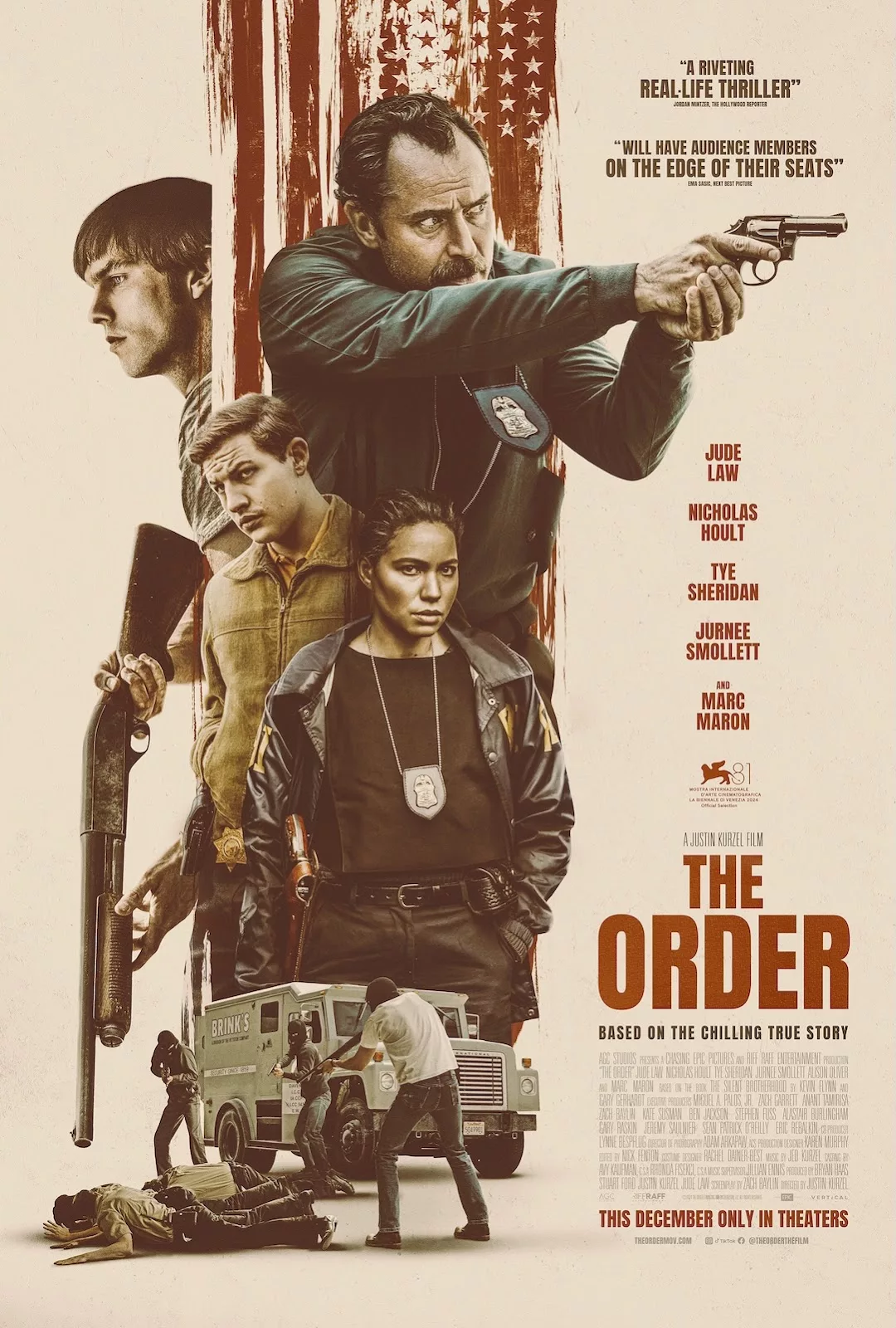

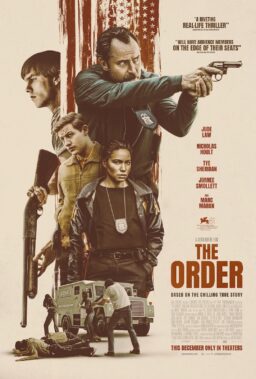

In director Justin Kurzel’s bracing investigative thriller “The Order,” Jude Law is at his scruffiest. As FBI Agent Terry Husk, he is literally a husk of his former self. His stout body is bent; his five o-clock is half-past nine; the gum he’s gnashing is a powdery dust. When he arrives in the quaint town of Coeur D’Alene, Idaho to investigate a disappearance, we’ve seen this type of character enough — a lonely law enforcement officer estranged from his family and filled with regret — that we know exactly how he’ll approach this case. He will tear it apart with fury.

Husk skulks around town, searching for clues to connect this disappearance with a rash of bank robberies and planted explosive devices that have littered the terrain. Jamie Bowen (Tye Sheridan), a go-get-em young officer, points Husk in the direction of the Aryan Nation compound just a few miles outside of town.

With its interest in cults amidst a rural landscape, many will probably connect “The Order” to “True Detective.” But that comparison feels too easy. The murderer of women in the first season of “True Detective” is so out of reach they border on impossibility. The gang in Kurzel’s film is painfully real and eerily present. Similar to contemporary white supremacists, they’re no longer content spewing their diatribes on secluded compounds. Young men like Bob Matthews (Nicholas Hoult) want to step from behind the cautious shadows of the prior generation, to enact a new world order that’ll be taken by force.

In DP Adam Arkapaw’s gorgeous photography of secluded landscapes blessed with a forlorn beauty, “The Order” often recalls Kurzel’s “The True History of the Kelly Gang.” That film married the unforgiving Australian terrain with the rageful spirit of anti-colonialist outlaws. In “The Order,” despite their own beliefs, these outlaws are decidedly not as principled. Their bigotry exists on the edge of the country, and it’s that perceived expulsion that further fuels their desire to break eastward to overthrow the government.

The film begins in 1983 with the combative voice of Jewish Colorado disc jockey Alan Berg (Marc Maron), verbally sparring with antisemitic callers. Before long, Kurzel and editor Nick Fenton take viewers into a car where two friends lead another compatriot to his execution at a remote spot in the woods. These two men will later join Matthews and another man in the hold-up of a bank. When Matthews returns home to his wife, his white shirt doused by an exploded red dye pack, she is not surprised. She is happy and relieved to see the duffle bag of cash.

Surprisingly, Law’s Husk spends large swaths of the nearly two-hour runtime off-screen. Instead, Kurzel stays alongside Matthews, carefully observing the execution of his plan. Dramatically, it’s a difficult task. Matthews is merely a zealot. As such, there is very little psychological range to explore that isn’t immediately knowable on the surface. For his part, Hoult doesn’t overplay Matthews; he portrays him as a self-anointed messianic figure who remains relatable and down to earth with his flock. His best scenes aren’t with the gang — which points to how dry that dynamic plays — they’re opposite Law.

That reality isn’t all-too surprising because everyone’s best moments in this film are opposite Law. There’s also a charged Jurnee Smollett as fellow FBI agent Joanne Carney and a committed Sheridan. Around a morose Law, the other two actors carve their own distinct edges to activate Husk’s emotional brokenness. But a different voltage vibrates when Law and Hoult are on screen together. Both are playing men who seem destined to die alone; they’re so alike, they’re even capable of predicting the other’s moves. Each actor’s performance feels that way too, mirroring each other so closely that even their similarly forced laughs reveal their chameleonic slipperiness in social spaces.

Their game of cat and mouse is further exemplified in the film’s tactility. Wood-paneled walls and seedy neon-lit bars, places where you can smell years of sweat and love, do more than replicate the time, they give us a sense of these characters’ inner demons. Matthews wants to be a family man but can’t stay away from the aluminum-plated warehouse where his weapons are stored; Husk spends his mornings washing his hands of his regret in the waters of a local creek. These touches keep the film grounded, even during the heart-pounding robberies Matthews and crew commits — leading to a tracking shot whose strong hold on composition and movement nearly caused me to sit up with the same attentiveness as when I first watched the much-longer, more elaborate track in “True Detective.”

Unlike most other true-crime films, “The Order” isn’t out to titillate or digress into exploitation. The film instead heeds to a strict hold on tone, mood and pacing that doesn’t aim to manipulate the viewer but to slowly unravel them to the point of feeling as hollowed out as Husk. In the process, it furiously tears us apart